Editor’s Note: To honor Johnny Cash Day on February 26, we are sharing Carmie Henry’ s behind-the-scenes take on the preservation of Cash’s boyhood home in Dyess.

This story is the second of two reflections from Carmie Henry on Johnny Cash’s enduring Arkansas legacy. To honor Johnny Cash Day on February 26, we are continuing Carmie’s story, sharing his behind-the-scenes take on the preservation of Cash’s boyhood home in Dyess. Read his first installment published last year, “From Dyess to DC” about the unveiling of the Johnny Cash statue in Washington, D.C., created by Arkansas artist Kevin Kresse. I had the pleasure of accompanying Carmie and his band of good-hearted preservationists around the Dyess Colony and the Johnny Cash Boyhood Home. It was humbling to witness this group of Delta visionaries come together in the very place they worked so hard to develop. Special thanks to ASU Heritage Sites Program staff, both currently serving and retired: Dr. Adam Long, executive director, Penny Toombs, assistant director, Will Reaves, director of the Historic Dyess Colon and Johnny Cash Boyhood Home, Dr. Ruth Hawkins, retired executive director, and Paula Miles, retired assistant director.

A post-holiday road trip by two music-fan friends ends up bringing new life to a charming little place called Dyess.

Written by Carmie Henry

Photographs by Logan Keown

I have a story to tell. It’s an Arkansas story about preserving history, making lifelong friends, and the legacy of a music icon.

My story begins on December 26th, 2008. I was vice president for governmental affairs for the Electric Cooperatives of Arkansas and my colleague Kirkley Thomas worked there in economic development. Originally from Lepanto in Poinsett County, Kirkley is an Elvis Presley trivia guru and graduate of Arkansas State University. Both of us were music fans. We wanted to drive over to Dyess to find the house Johnny Cash grew up in. We knew it was standing and occupied by a retired heavy equipment operator. The day after Christmas seemed like a good time to make the two-hour drive. Offices were closed, gifts had been opened, and family had departed. With no sporting events on TV, we knew we’d be bored.

We arrived at the town center of Dyess around mid-morning and stopped to look at the old community building where Eleanor Roosevelt spoke to 500 people at the dedication of the town. Her husband’s New Deal was responsible for this community. For some time, it became a thriving, if small, farming community. But by 2008, Dyess was a dusty, dying delta community trying to hang on. Most of the original family farms that provided a way of life for folks like the Cashes in the 1930’s, 40’s and 50’s had given way to consolidation into larger farm organizations and corporate farming. The families had mostly moved off or died out.

While Kirkley and I were standing in front of the old administration building reading a plaque commemorating the town’s history, we were approached by a gentleman who asked us if we knew where Johnny Cash’s house was; we responded that we did and were just about to drive to it, if he’d like to follow. The man said that he and his wife were from Canada. They had traveled to Nashville, on through Memphis, and were headed to Branson, Missouri, on their own country music tour. They were pretty adventurous to find Dyess.

The drive out the dirt road from downtown Dyess was short. The Cash children probably walked that road back and forth many times when Johnny’s younger brother Tommy was a projectionist at the “movie house.” We arrived and parked on the narrow road to take a look around. A hand-lettered sign on a piece of cardboard tacked to a stake in the ground said: “Pictures $5”; the owner was well aware of whose house he had been living in for the last thirty-eight years.

The wooden house was ramshackle. It needed a new roof and hadn’t been painted in years. Recent rains left puddles in low spots in the yard. Farm implements lay untended. I was halfway expecting some grumpy old man in overalls wielding a shotgun to open the front door demanding his $5 fee. No one emerged, but out of respect, we did not get too close.

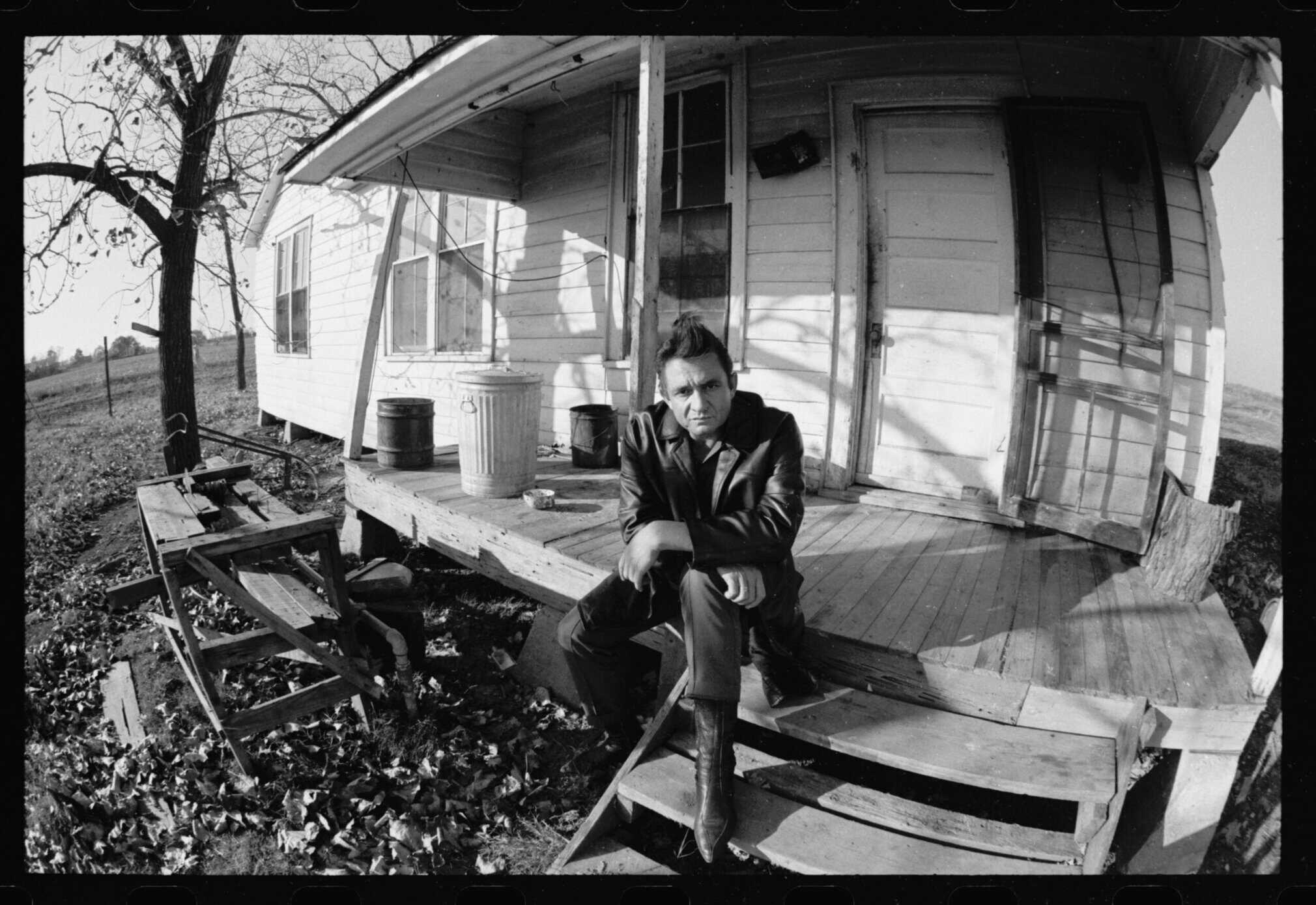

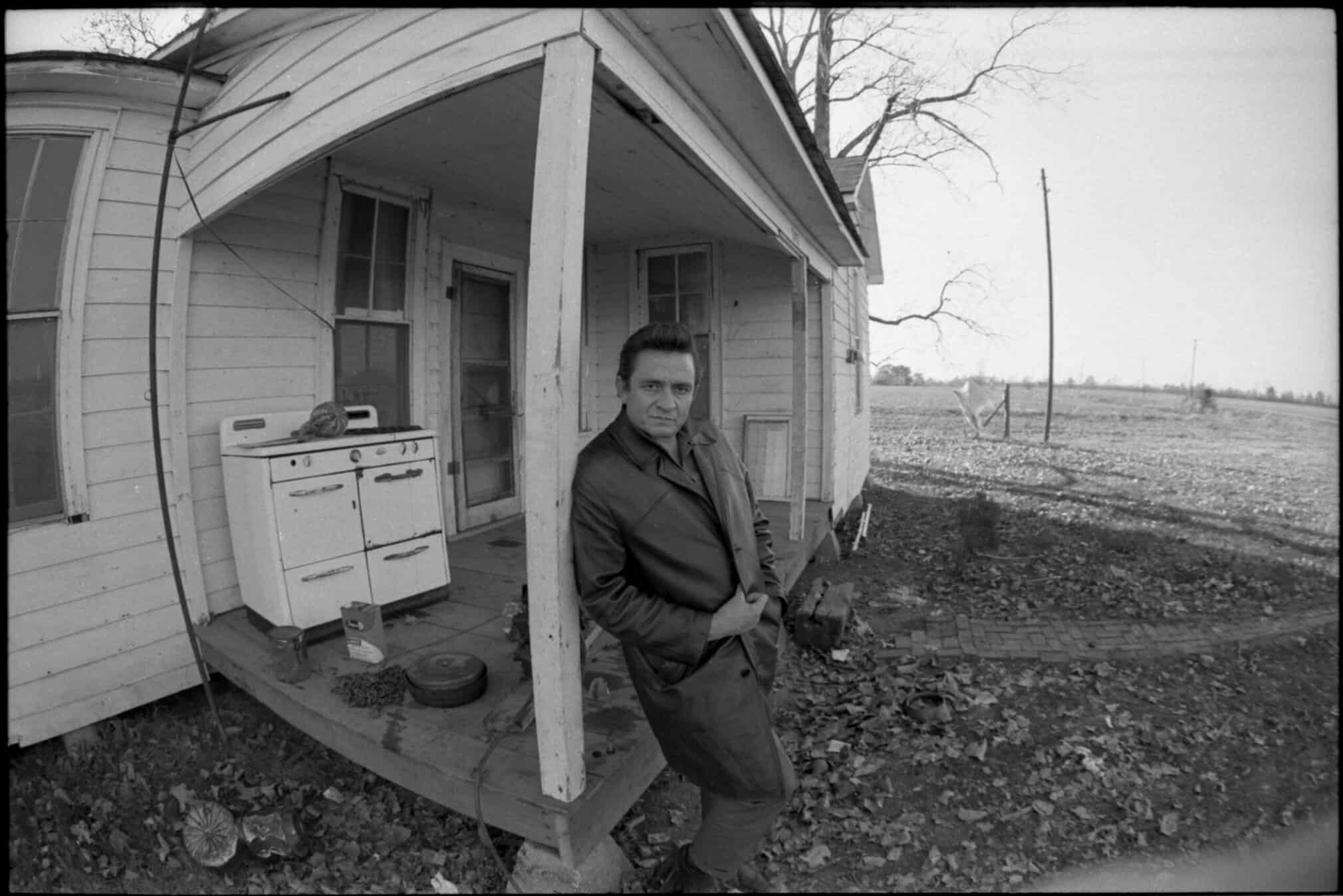

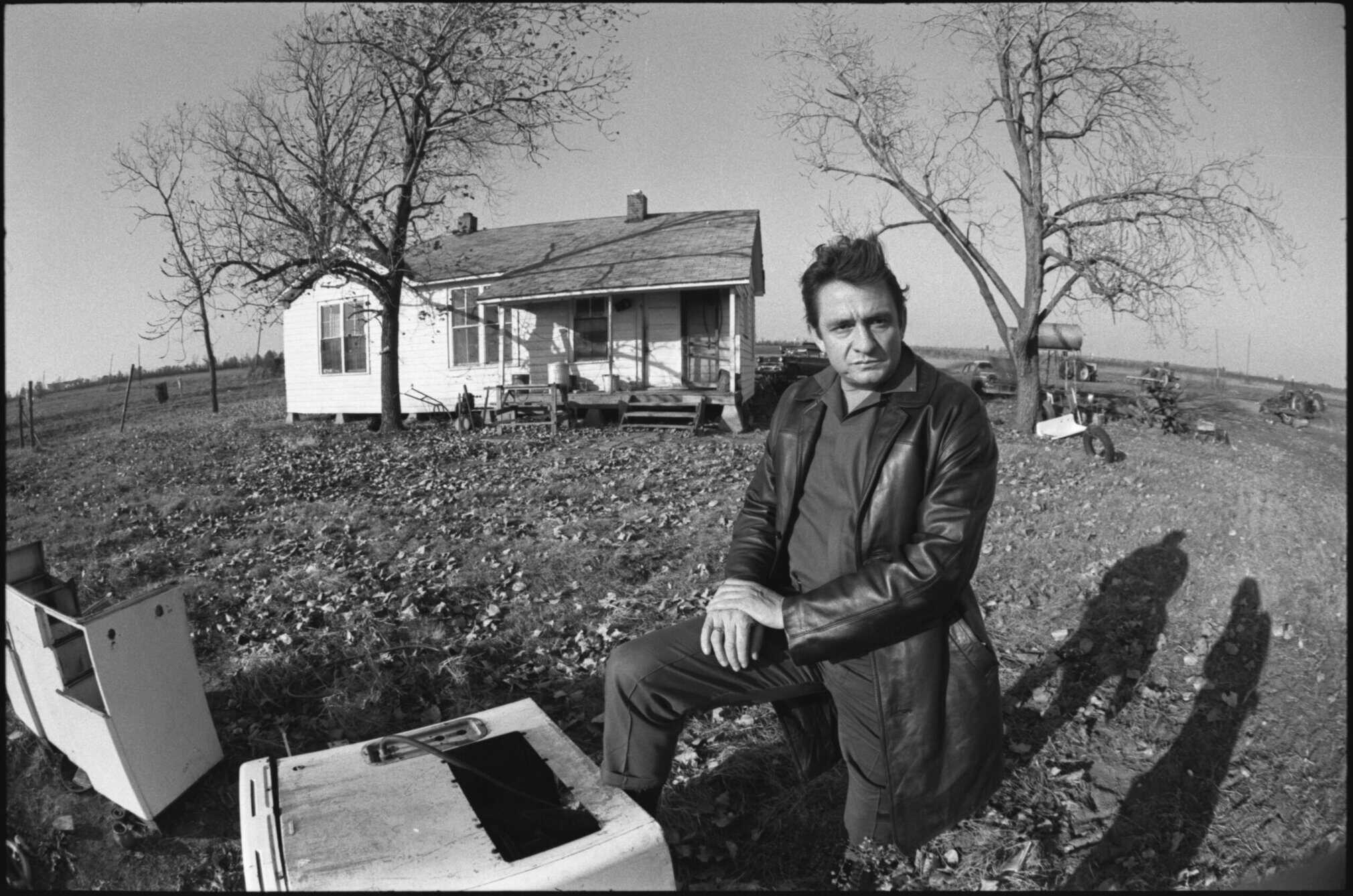

Images courtesy of the Library of Congress. Baldwin, Joel, photographer. Image from LOOK – Job 68- titled Johnny Cash. United States Arkansas, 1968. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016718833/

After several minutes of searching from afar for any clue of what the place might have looked like when the Cash family lived there, we returned to our car and drove on toward Memphis. We toured Sun Records, the famous studio where Johnny cut his first record. Before heading home we ate lunch at the world famous Charlie Vergos The Rendezvous restaurant.

On the way home, Kirkley and I did not stop talking about this opportunity to preserve a piece of Arkansas history. If a couple from Canada were willing to stop by Dyess to look at Johnny Cash’s boyhood home, wouldn’t others? There is economic potential in tourism. We would later learn that people from many, many states have traveled to Dyess to see the Cash home. (A tour bus with travelers from Ireland had even stopped by.)

There was only a shack to look at. Nothing faintly resembling the well-kept house the family had called home.

Kirkley remembered his alma mater, Arkansas State University, played a significant role in in the preservation of the Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum and Educational Center in Piggott (Clay County), where in 1928 Ernest Hemingway wrote significant portions of A Farewell to Arms. The Arkansas State University (ASU) Heritage Sites program had also started the Southern Tenant Farmers Museum in Tyronza (Poinsett County), and preserved the Lakeport Plantation in Lake Village (Chicot County).

Enter Dr. Ruth Hawkins. Kirkley knew Ruth enough to place a phone call. Ruth, an advocate for historic preservation, was the director of the Arkansas State University Heritage Sites Program at the time. That would be our game plan: Call Ruth after the holidays. Dr. Hawkins took Kirkley’s call and in January 2009, agreed to meet with us. We determined that acquisition of the property (which was not listed for sale) and the renovations required to get it ready for tourist traffic would be costly and there was no immediate source of revenue in sight. It would take getting the Cash family interested and involved. Who could do that?

Inside the dining room in the preserved Cash home, left to right: Kirkley Thomas, Carmie Henry, Dr. Ruth Hawkins and Paula Miles.

Ruth and her industrious staff conducted all the research and it wasn’t long before this little project became a shared obsession. Ruth’s ASU team included Paula Miles who was the assistant director of ASU Heritage Site program (she is now retired), Dr. Adam Long, who was director of the Pfeiffer-Hemingway Museum then and is now the executive director of the ASU Heritage Sites Program, and Penny Toombs, who is now assistant director for the program, plus countless others who helped. The property was occupied by a lone, elderly man who had lived in the house for decades. We learned he had a son in Little Rock and an ex-wife living in Osceola who might provide some insight.

City officials and local residents were consulted. Mayor Larry Sims was enthusiastic, sharing his stories of tourists in search of the Cash home. We learned the movie “Walk the Line” starring Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon increased interest in Cash family lore and the son of the man living in the home had decided that the property was worth big bucks. This was not going to be easy. We had no money, no authority, and no guidance. We did have a clear vision, though, so we waded in.

Early on, we ran into some luck. Kirkley’s son played little league baseball and one afternoon at practice he engaged another parent, State Senator Steve Bryles, in conversation. Talk turned to Dyess. The house was close enough to his senate district boundaries to get him interested, so the late Senator Bryles directed general improvement funds or GIF money to a feasibility study so that we would know what our project would take to get off the ground.

Dr. Ruth Hawkins points out the kitchen window to the spot in the yard where Johnny’s mother first heard him sing.

Naturally, the study took time. Weeks turned into months. Months became years. Without acquisition of the house, the project couldn’t go anywhere. Negotiations with the homeowner’s son were not progressing, but Ruth’s team was a beehive of action and ideas. We knew if the property were to be purchased, we needed to raise funds. The home required preservation and repair work before it could ever be shown.

Enter Bill Carter. An Arkansas native and lawyer for the Rolling Stones, Bill was mostly retired and living near Nashville in Lebanon, Tennessee. He was the guy who bailed Keith Richards out of the Fordyce city jail some 50 years ago. He’d gotten that job through a quirk of fate thanks to longtime Arkansas Congressman Wilbur Mills who helped the band with a messy legal issue during an American tour in the 1970s. He also happened to be the Executive Producer for Gaither Television Productions. Many of the Gaither-produced shows aired on local PBS stations. (This connection would prove useful later on.)

Bill knows how to motivate folks. He suggested Ruth go to the mayor, pick a piece of ground near the Dyess city limits and erect a large advertising sign that read: “Future Location of Johnny Cash Boyhood Home Restoration Project,” complete with surveyor yellow tape and stakes. It did not take long. The idea that ASU was going to proceed with or without the actual property pushed the owners and the sale was made. A huge hurdle was cleared.

We were committed now. No turning back. With Bill’s help, Ruth connected with Rosanne Cash and John Carter Cash, two of Johnny’s five children. Restoration of the homesite was going to be complicated and expensive. The gumbo soil of the delta region made for unstable building foundations. The house had to be lifted so a more compact fill could stabilize the ground in the house’s original plot.

Fortunately, two of Johnny’s siblings, Tommy Cash and Joanna Yates, became engaged with the project and helped the restoration team return the house to look like the Cash family home. They were even able to provide the original piano the Cash family matriarch, Carrie Cash, played for family gospel singalongs.

With the blessing and promised participation of both Rosanne and John Carter Cash, we started planning the first fundraising concert. With artists as varied as Kris Kristofferson, George Jones, Dailey and Vincent, Rodney Crowell, and Gary Morris, the draw was enough to fill the ASU Convocation Center. Rosanne and John Carter served as co-hosts and performed.

Carmie and Paula admire a treasure from Johnny Cash’s childhood and Kirkley inspects a piece of dinnerware manufactured at a local factory in Dyess that is on display in the dining room.

So in 2011, just three years after our first drive to Dyess, the ASU campus was alive with music fans anxious to hear tributes to Johnny Cash. The evening was marred with only one sad announcement: Johnny Cash’s original bass player, Marshall Grant, one of the original Tennessee Two, was in Jonesboro that day and suffered a fatal stroke.

The fundraising concert was filmed and later played on PBS, thanks to Bill Carter’s Gaither Productions connections. Subsequent concerts were organized on the ASU campus in 2012, 2013, and 2014. Rosanne and John Carter continued to be involved. Willie Nelson, Reba McEntire and other country music celebrities participated.

With a lot of hard work (and some luck), the Cash family home was finally restored. Even the downtown Dyess community center was improved and exhibits placed there detailing the history of the original New Deal colony.

Top, left to right: The dining room, kitchen and living room. Bottom: Johnny’s siblings bedroom. The entire home has been preserved and is part of the ASU Heritage Site Program.

With the house ready to be shown, the decision was made to hold the 2016 concert outdoors in the fall, in an empty field next to the house. Rosanne and Kris Kristofferson headlined and once again, it was a sellout. The optics of Johnny’s daughter and fellow Highwayman singing next to his boyhood home on a bright fall afternoon conveyed a slice of Americana not often seen these days. Johnny’s nephew Roy Cash, a former Navy fighter pilot and author of one of Johnny’s most beloved songs, “I Still Miss Someone”, sang with his daughter and former Miss America Kellye Cash.

You had to be there.

The outdoor venue was used twice more for larger shows, but nowadays the fundraisers have become more intimate affairs. Rosanne brings in a favorite singer/songwriter and performs at the Sunken Lands Songwriting Circle and continues to honor Johnny Cash’s musical legacy.

Johnny Cash passed away in September of 2003, nearly 23 years ago. While his memory will never be forgotten, it took the Arkansas General Assembly to put the finishing touches on his legacy. It is entirely reasonable to acknowledge that without the efforts of Dr. Ruth Hawkins and the staff of Arkansas State University to preserve this valuable piece of Arkansas history elevating the Cash name back into the public consciousness there likely would be no statue of Johnny Cash in our nation’s Capitol.

Birthday Celebration of Johnny Cash

In recognition of Johnny Cash’s birthday on February 26, Historic Dyess Colony: Johnny Cash Boyhood Home will be giving free tours all day and serving desserts from Mama Cash’s recipes. You can find more events and programs at the historic site on the events page.

Carmie Henry is a storyteller and Arkansan with more than 22 years of experience on the staffs of three United States senators and an Arkansas Secretary of State. He received a bachelor’s degree in accounting from the University of Central Arkansas and is a retired Naval Flight Officer with the rank of Captain with nearly 200 combat missions in the Vietnam War flying from the USS Enterprise.

T. Logan Keown is a photojournalist and visual artist whose work is shaped by honesty and curiosity. A veteran with nearly a decade of service in the U.S. Navy as a Mass Communication Specialist, his award-winning photography blends technical skill with a storyteller’s heart. Originally from Arkansas, Logan is reconnecting with the place that shaped him and spending time nurturing creative projects. Follow him on Instagram and find his work online.