Winding roads, family roots, and finding home.

Around the time I pass through Bee Branch, the quirky town near Greers Ferry Lake, the cattle pastures of central Arkansas give way to what was once an ancient plateau. I wind through long switchbacks and creep up in altitude. It’s a sneaky climb, and if you’re not paying attention, you can miss the experience.

Long ago, this land was a mesa. What emerges before me now are gentle peaks and valleys — the Ozarks — which water and time have carved into something of a mountain range, but also something different.

It’s late December and shadowy gray clouds blot out the sun. There’s a heavy mist coming down but somehow it’s still beautiful, achy almost. I feel a deep sense of longing, a thirst for primitive beauty. I think about the opposite equinox and how next year this stretch of highway will flood with party barges and lake people smelling of sunscreen and summer. But today, it’s sleepy out. Blurry and wet. Quiet.

There are more diminutive pieces of farm land along the roadside now. I spot cattle, horses, chickens. Animal husbandry defines Ozark agriculture because the land is inhospitable to crops; it takes grit to live in these parts, which lack fertile soil and quick thoroughfares. Winding county roads hug the rugged landscape, and for the willing, each stop offers its own treasure for the patient and curious traveler.

Bee Branch looks like it could be the town that birthed the first Sonic Drive-In. It’s charming; old grain silos and mill equipment flank the road, its shoulders heavy with flea markets signs and kitschy garden ornaments made from scrap metal. I sneak farther north, and the morning’s opaque mist lifts a little, revealing sweeping Ozark vistas, valleys, and hollers. I spy hideouts for hillbillies tucked into the mountainside, humble dwellings of those who know what it takes to make a life here.

This land requires a different kind of tenacity than other places in the state, and that is neither good nor bad. To be honest, I never felt connected to the land in Arkansas when I was younger. I was told my father’s family came from the heart of the Ouachitas down in Garland and Hot Spring Counties. Dense, tall forests of shortleaf pine blanket the ground in needles there. The forest is farmed at every turn, and the highways are clogged with menacing tractor trailers, hauling logs that threaten to spill at the next pothole.

Growing up we spent Thanksgiving holidays just outside of Malvern, another town where the Sonic Drive-In could have been born. Beside the highway sat my grandma’s trailer, which smelled of mothballs and pine cones. When we’d visit, my sister and I would make mud pies with old plastic planter trays. My great uncle lived on the other side of the road, which we were forbidden to cross lest we get hit by a car. His home was a pre-war shotgun with bad lighting. It had just a few bedrooms and more than a few taxidermied deer whose faux dead eyes followed my every move. The yard was spacious with buried vintage cars and tractors. There was also an old school bus where my second cousin slept. My dad’s people were money-poor but rich with family, ritual, and pie.

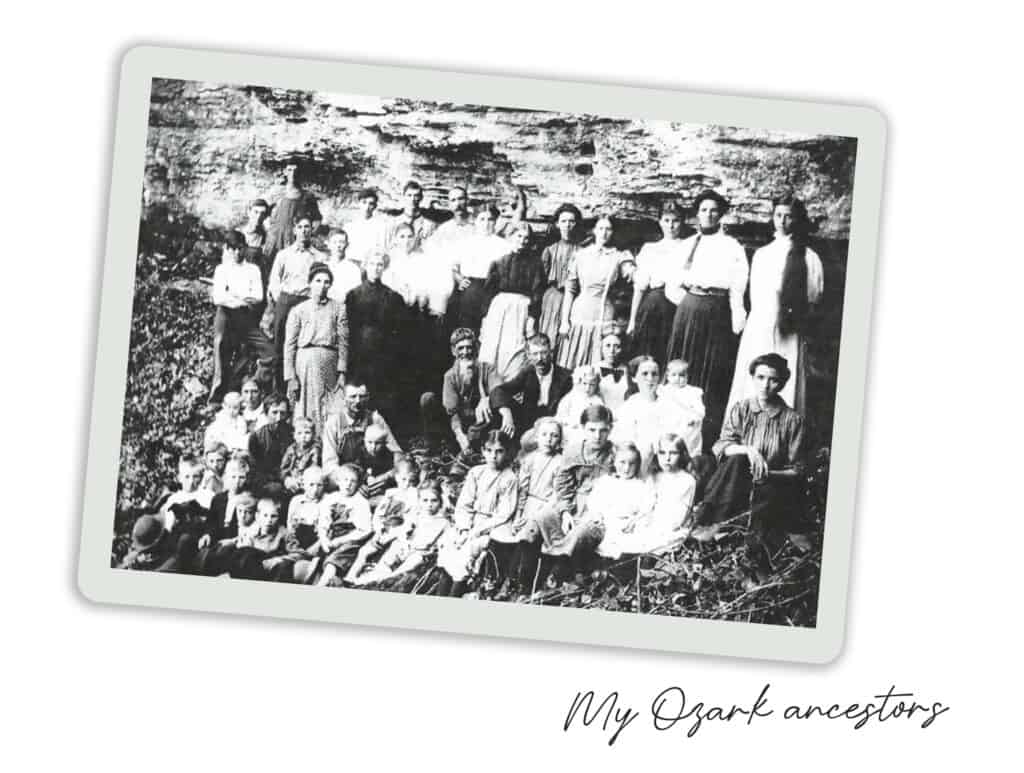

Even then Arkansas didn’t feel like home. But this changed the first time I laid eyes on the Ozarks. What I felt then was what I feel right now — that sense of achy longing, a bewitchment with its melancholy. It’s a curiosity to explore and understand. It’s a profound sense of place and time, sandwiched in ancient layers of shale and limestone. A few years ago, because of my sister’s diligent research, we learned that my father’s people are actually Ozarkian. I now have a photo of my 19th century ancestors posing along the edge of a bluff shelter— a revelatory confirmation of my place in the Ozarks.

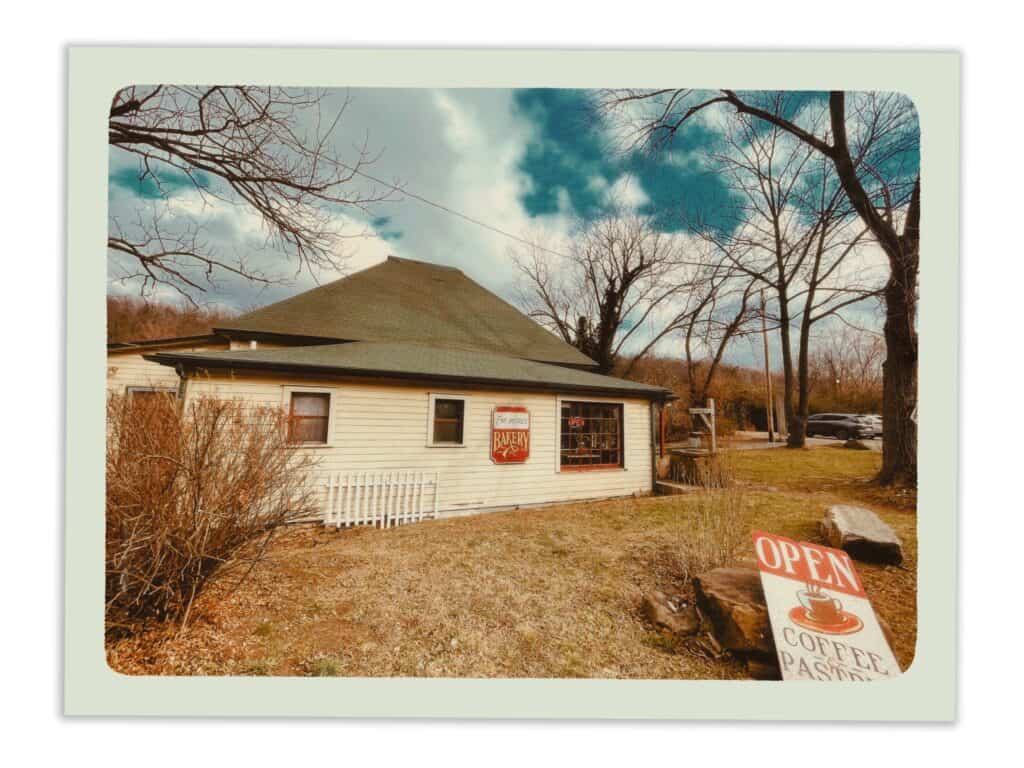

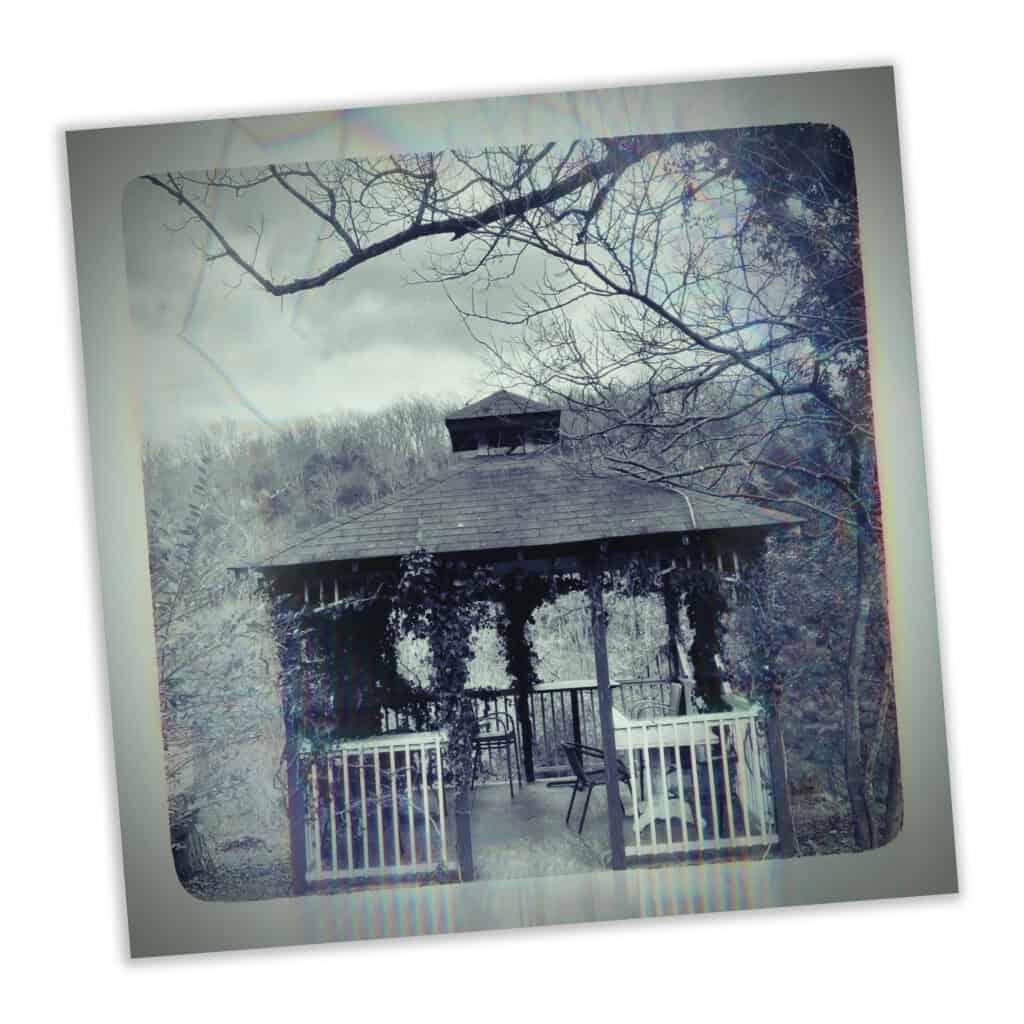

Highway 65 turns into two lanes, and I start a curving descent into a valley. My ears pop from the forgiving attitude change. Just as the sun breaks through the clouds, I’m officially in the Ozarks. A mile up ahead is the Serenity Farm Bread bakery, the point of my detour on my way home to Fayetteville. Serenity sells crusty loaves of sourdough bread made via bygone methods. The bakery and its provisions exude hillbilly hippie, two identities that are not mutually exclusive. Rather, they compliment quite nicely. I think of the book my friend Jared wrote about the counter-cultural bohemians who forged a land revolution in these parts. Are Ozarkians the original hippies? Perhaps.

The bakery is in an old, pale yellow farmhouse with a green roof. It’s the Saturday before Christmas, and they’ve sold out of nearly all their bread. What’s left is Ozark black apple walnut. I pick up a few danishes and some oatmeal raisin cookies, also made with sourdough. I buy a funky piece of pottery. A couple of locals pop in to grab a pastry and lightheartedly complain about the holiday traffic. The highway seems quiet enough to me, but I suppose even a sporadic stream of cars makes it feel congested this time of year.

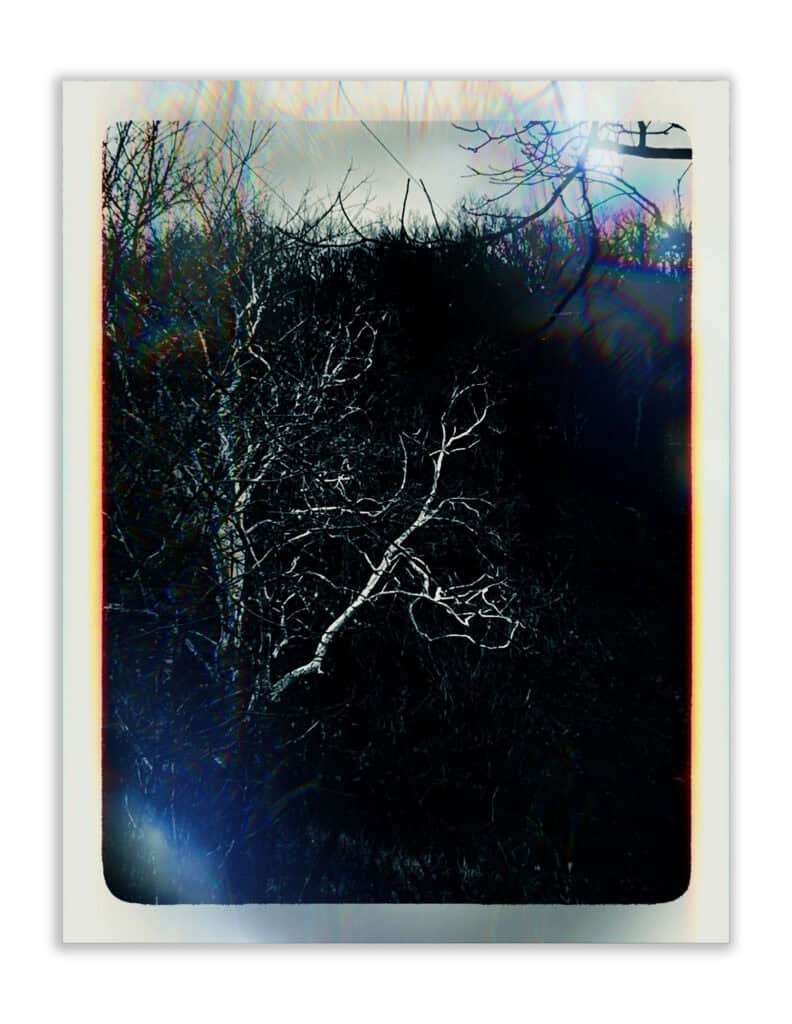

Behind the farmhouse, lower in the valley, a striking pale oak tree catches my eye. It’s bleach white and looks like a static lightning bolt that’s suspended in midair. The albino bark is probably caused by some kind of parasite or fungus, but the tree stirs up that achy longing in me, that bewitchment. What stories does it hold? What changes has it seen during its long life? I linger for a minute or two, staring with curiosity and wistfulness.

Despite being stripped bare, the tree is hauntingly beautiful. It’s knotted, tangled, and without its skin. It’s vulnerable, yet it endures.

What, I ask myself, is more Ozark than that?