It was sunny and warm when we made the plan to meet at the flagpole of the Upper Elementary School, and sit outside to chat. But a cold wind blew in. So when I pulled up and saw her standing there shivering, I motioned her over to sit in my car. She did.

She was tiny. The same age as my 15-year-old Adelaide, but several inches shorter. Eyes the color of whisky; hair the color of wheat. Dressed in sweats and a t-shirt like any other teenager. Alabaster skin, little pearls for teeth. The only thing severe at all about her, the only thing not childlike, was her eyebrows. They swept across the top of her face like two long, elegant brushstrokes, high and arched.

Olena Havrylova lives with her parents, Sergei and Yulia, in a town of 90,000 called Lisichansk in the Donbas region of Ukraine. Her brother, Daniil, 19, is a student at the University in Kyiv.

I wanted to hug her because that’s what I do. And her mother is an ocean away. But she regarded me a little bit like a scared rabbit, so I refrained.

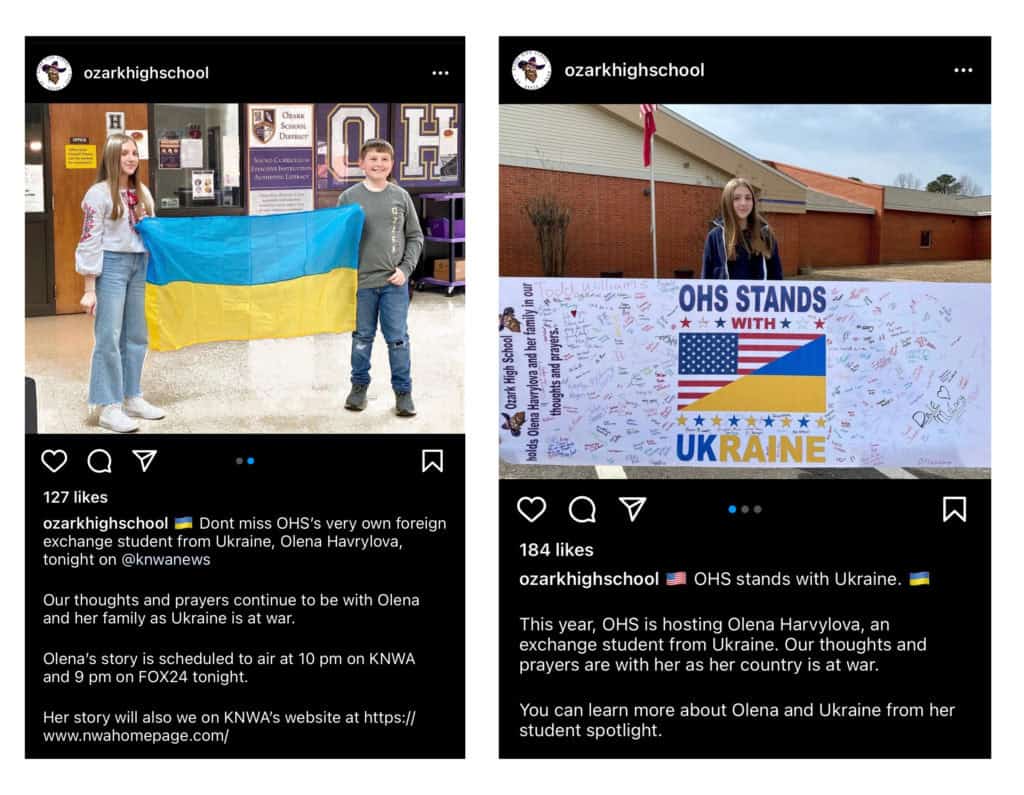

We talked about nothing at first. She likes it here; loves the people. The people are very friendly. Her host family is good to her. She likes the school. “I feel big support here.” She smiles. The high school made a poster for me.”

“What was it like,” I asked her, “when you heard the news of the Russian invasion?”

She nodded, anticipating the question. “I was very surprised. What I mean is, there has been war in my country since 2014. So there are always threats, and sometimes soldiers and sounds of fighting. We kinda got used to it, and you might have to be careful a few days, and then everything would be normal again. But everybody didn’t expect this to happen.”

Olena Havrylova lives with her parents, Sergei and Yulia, in a town of 90,000 called Lisichansk in the Donbas region of Ukraine. Her brother, Daniil, 19, is a student at the University in Kyiv. Because of Covid, he’s been home for three months, scheduled to go back to Kyiv in February. But Covid numbers started climbing again so the university extended quarantine. Olena is grateful he was home with the family instead of in Kyiv when the bombing began.

“Putin didn’t know how strong we are. He thought he could just come in and take our land, that Ukraine would allow it. But that will never happen.”

The Donbas region is in the far east of Ukraine, bordering Russia. She said for now the fighting has died down in her town, but her family still keeps their windows boarded. They live on the first floor of a nine-floor building. There’s a basement in the building the residents use as a bomb shelter. Her school is across the street, and also has a basement in which neighborhood folks can hide. She showed me a picture of her school, and the street in front of it, where a rocket sticks up out of the blast it made in the pavement. It looks like some weird sculpture, a macabre artistic statement. Her grandparents live five minutes away.

She showed me another picture. “This is a free train. It is taking women and children to L’viv.” The hoards of people lined up on either side of the tracks reminded me, eerily, of old photos from World War Two. “From L’viv they must get a car to take them to the Polish border. It’s a dangerous journey.”

Olena explained that her mother could leave if she wanted to, but the men—her son and husband—must stay. So she is staying. “The men have to stay and fight,” Olena said. “If they try to leave, they will be caught and immediately drafted.”

I asked Olena what she thinks about the Russian people. Does she see them as her enemies? “I feel sorry for them,” she said. “All they have is fake news. Putin tells them their army is going to my country to help us, because we are fighting each other. Even the soldiers didn’t know the truth until they crossed the border. That’s when they were given the order to shoot us.” She told me her best friend’s brother studies in Russia and he believes the fake news. “It is crazy. So sad.”

Leary of fake news myself, I asked her if our impression of Zelensky—as the brave, beloved, heroic leader—is accurate. “Oh yes,” she exclaimed. “We love him. The whole country is behind him.” She shows me a video of Putin surrounded by fake people, in front of a background she says is fake, then one of Zelensky. “See how he moves the microphone? That is to let us know it is real, he is right there in his office. He will not leave us. He fights with our army, while Putin stays hidden.”

Olena, who shares a first name with Ukraine’s first lady, swells with pride as she continues. And I understand that the image of fierce, patriotic Ukranians I’m seeing on Twitter and CBS is not fake news either. “What do you think will happen?” I asked her.

“I think we will win.” She looks into my eyes. Hers are suddenly very serious. “Putin didn’t know how strong we are. He thought he could just come in and take our land, that Ukraine would allow it. But that will never happen.”