The story of public libraries in Arkansas is shaped by the

persistence of women’s groups and local citizens who transformed community-driven efforts into a statewide network of libraries.

Written by David Sesser

Development of public libraries in Arkansas progressed slowly in the early twentieth century, with efforts often led by local women’s organizations. At a meeting of the American Legion Auxiliary held in the midst of the Great Depression, conversation included efforts in various states regarding the establishment of libraries. The attendee discussion turned to criticism as Arkansas, with only three operational public libraries, was deemed to be “the most bookless state in the union,” and organization members from the state were admonished to return home and remedy the situation. Led by Adolphine Fletcher Terry, the auxiliary members from Arkansas accepted the challenge and sprang into action, creating a system of libraries that continues to serve the citizens of the state in 2025.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt (left), guest of honor at a 73rd Club luncheon in Washington, D.C., speaks with Adolphine Fletcher Terry (right) on March 23, 1940. Terry, wife of Congressman David Dickson Terry, served as president of the club, which was composed of wives of Congressional delegates. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress: Harris & Ewing, photographer.

A common theme among Arkansas public libraries is a constant striving for excellence in the face of immense adversity.

Despite a seemingly disinterested government and populace, librarians in the state continue to work hard and offer a wide range of resources to their patrons. These efforts have created a resilient library system in the state, in spite of reduced budgets and a never-ending fight to prove their worth. By examining the history of libraries in the state, we understand how our current system of public libraries came into being and gain clues about the future direction of the institutions.

Private Collections, Public Need

Located in private homes, the earliest libraries in what would become Arkansas often contained only a few volumes due to the difficulty of transporting books from Europe. In the early nineteenth century, private lending libraries began operating in several towns in the state, including in Hot Springs and Little Rock. Notable Arkansans operated these libraries, including William Woodruff in Little Rock and Hiram Whittington in Hot Springs. These libraries required patrons to pay an annual fee to utilize resources, making access to books well out of reach for the majority of the population. The library created by Woodruff operated until the Civil War period when a fire and subsequent theft of many books by Federal soldiers ceased its operation.

In the postbellum period, various private libraries once again flourished in Little Rock and other larger cities, although access continued to be restricted and none of the establishments could be known as truly public in nature. This changed when various women’s groups across the state began working to create libraries in their home communities. In 1897, the Women’s Cooperative Association created a library housed in the Arsenal Building, now known as the MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History. The Pathfinder Club of Morrilton created a library collection that rotated among the homes of club members, offering patrons an opportunity to borrow books. Women’s clubs created a total of 28 libraries across the state between 1880 and 1935.

The efforts of these women created the basis for the modern public libraries in operation today.

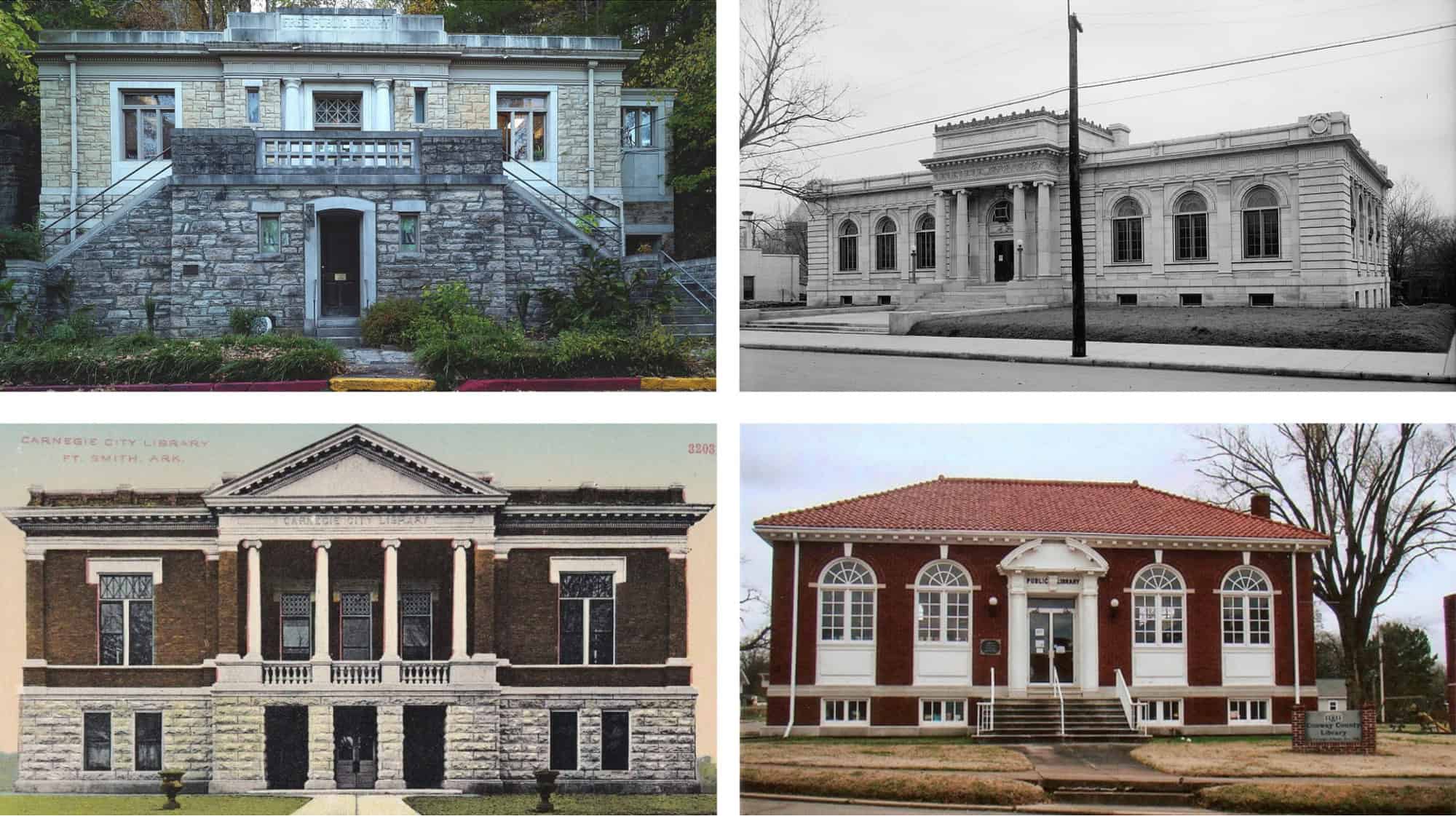

Legislation helped make these private efforts more available to other residents when the Arkansas General Assembly passed a bill that allowed cities to collect a millage to support library services. The Carnegie Foundation provided funding to construct four libraries in Arkansas, with locations in Little Rock, Morrilton, Eureka Springs, and Fort Smith. As of 2025, the buildings in Eureka Springs and Morrilton continue to operate as libraries.

Four libraries built in Arkansas between 1906 and 1915 using grants from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie are classified as “Carnegie Libraries.” Top left to right: Eureka Springs in Carroll County and Little Rock in Pulaski County; images courtesy of the Library of Congress. Bottom left to right: Fort Smith in Sebastian County; image courtesy of the Fort Smith Public Library official website and Morrilton in Conway County; image courtesy of the Conway County Library official website.

Other communities created their own library buildings using a variety of funding sources. Women’s Library Association in Arkadelphia raised one thousand dollars and borrowed another three thousand to construct a purpose-built library in 1903. The group toiled another decade to retire the debt.

Additional support from the state came in 1923 following the 1921 creation of the Free Library Service Bureau as part of the Department of Education. Efforts focused on helping local governments create libraries with some work toward establishing school libraries, but the Great Depression led to a reduction in funding and the organization ceased operations in 1933.

While it was operational, the commission worked with local governments to establish and support public libraries. It also created a level of professionalism amongst librarians in the state, eventually requiring all Arkansas library directors to attain a graduate degree accredited by the American Library Association.

Lobbying by various women’s groups pushed the General Assembly to create the State Library Commission in 1935 but monetary issues prevented funding the agency until 1937.

Barriers to Access and Efforts to Expand

Even with the creation of publicly funded libraries in communities across Arkansas, many citizens could not utilize their resources. Library services remained segregated for decades and Black Americans could not access the public facilities. Little Rock created a branch library in 1917 to serve the Ninth Street community, the hub of Black life in the city, and a larger facility replaced it in 1941. The Little Rock Public Library became one of the first in the South to desegregate with Black Arkansans utilizing the main library alongside white patrons in 1951, four years before the Brown v. Board of Education decision to end segregation in public schools.

Not all libraries constructed in Arkansas fit the idea that many people have of the institutions.

Communities often included libraries tucked away in the corner of a local county or municipal building, a forgotten resource to elected officials but a lifeline for patrons. Even purpose-built libraries could be tiny. The Norman Public Library, located in the Montgomery County town, is known as the smallest freestanding library in the state and likely the country. The tiny brick building in the town park was the result of a women-led fundraising effort by the Norman Garden Club to construct the building in 1935.

Courtesy of the Encyclopedia of Arkansas/

Photo by Mike Keckhaver.

The public library at Norman was once listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the smallest free-standing library in the United States. In 1993, the Norman town square and park, including the library, was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The rugged geography and isolated nature of many homes in the state made offering library services difficult. To offset these issues, many systems offered book mobile services to their residents, created branch libraries, or offered a drop-off system for residents in far flung corners of the state to access materials. Ted Richmond, a resident of Newton County, famously created the Wilderness Library in the 1930s. Based in a log cabin, Richmond relied on donations of books and magazines to share with local residents, often walking for hours from one mountain homestead to the next to deliver reading materials. HIs efforts received national attention after the Saturday Evening Post published an article in 1952 about the Wilderness Library, although some were frustrated about the image the article projected to a national audience about Arkansans’ lifestyles.

Growth, Modernization, and Community Role Today

The public libraries in Arkansas grew and expanded throughout the twentieth century; by 2000, every county in the state enjoyed at least one public library facility. The state library continued to provide resources, including funding for many of the libraries. Regional library systems help bring small libraries together to pool resources and offer better services for residents in nearby counties. Digital tools have broadened access for patrons, but libraries remain essential community hubs—offering everything from tool loan programs to job application support.

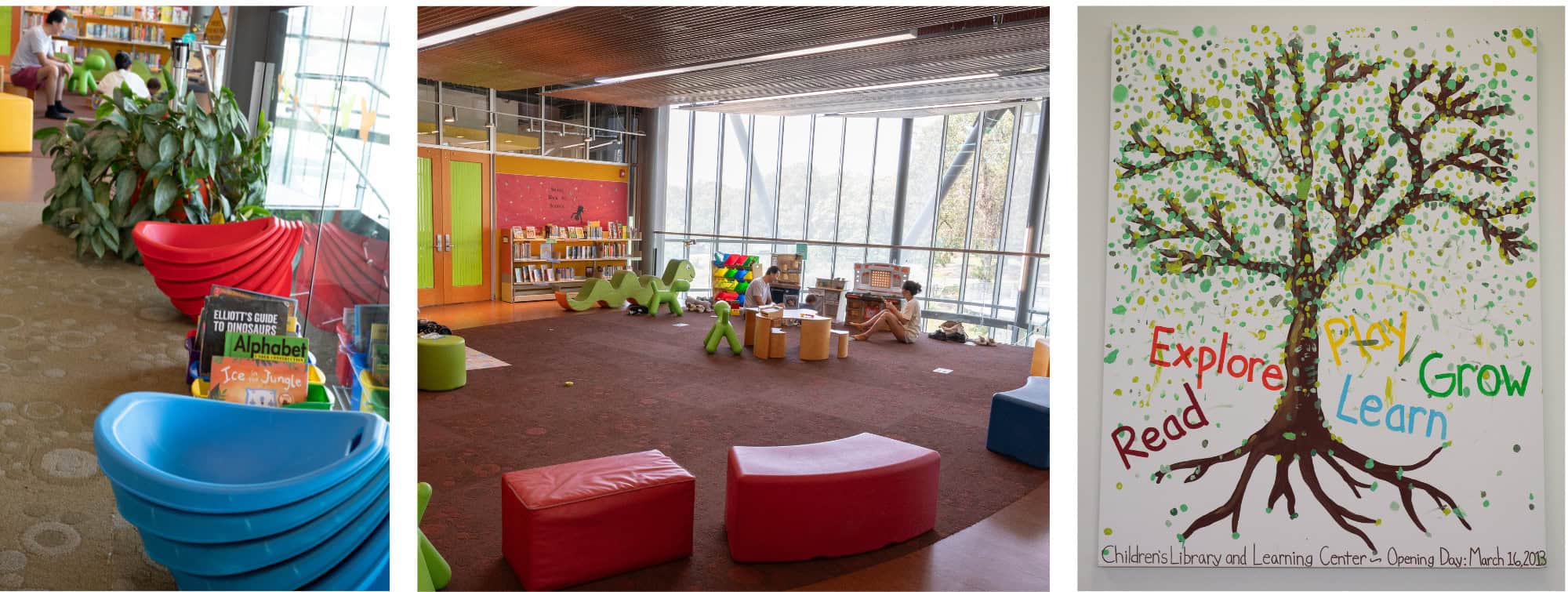

By 2025, Arkansas includes some of the most advanced libraries in the country. The Hillary Rodham Clinton Children’s Library & Learning Center in Little Rock (pictured above) serves as an example of how libraries can offer so much more than information resources with a teaching kitchen, walking trails, and theater housed on the grounds. The Fayetteville Public Library (pictured below) contains different sections for preschoolers, grade school students, teens, and adults, as well as a center for innovation. But just as important are the libraries in Stamps, Hazen, Waldron, and countless other small towns across Arkansas.

Building public libraries has been a community effort for centuries and today, they are needed more than ever.

David Sesser is the director of Sims Memorial Library at Southeastern Louisiana University. He earned degrees at Henderson State University, the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, and the University of Southern Mississippi. Sesser formerly served as a librarian at Henderson and as the chair of the Clark County Library Board. He resides in Tangipahoa Parish, Louisiana, with his wife and son.