As a young pastor and doctoral student in Nashville, Tennessee, the 1979 Southern Baptist Convention meeting in Houston was my second to attend. Knowing we would be electing a new president, generally for what would be a two-year term, I was especially interested in discovering who would be leading the largest Protestant denomination in the world (though Southern Baptists have traditionally eschewed the tag of “Protestant,” it aptly describes their mindset).

I was born-and-bred in the Southern Baptist way of life, and had learned that the SBC was a wide theological tent. There were those encamped in what was considered both the extreme left and extreme right, but by and large Southern Baptists dwelt in the huge middle… some to the left of center and others to the right, but still the center. What held us together was our common love for missions and sharing the gospel, reflected in what was known as the Cooperative Program.

SBC churches were encouraged to give a portion of their income to the Cooperative Program (CP), and from this central fund missionaries were supported, agencies received their funding, and seminary students like myself were provided essentially a free theological education. As a graduate of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, I felt my master’s degree was an excellent springboard for what I hoped would be a long and fruitful pastoral ministry.

It was a show of raw politics, never before seen in Southern Baptist life.

Little did we know what awaited us in Houston. I was sitting with Randel Everett, my best friend during our days at Ouachita Baptist University in Arkadelphia, high in the upper reaches of the Astrodome. Randel had gone to seminary in Fort Worth, and we hadn’t seen each other in several years, so we were enjoying our reunion. It came time for those who would nominate presidential wanna-be’s, and Adrian Rogers’s name was brought forth. Rogers was pastor of the huge Bellevue church in Memphis, and was, as both Randel and I agreed, unelectable because he was on that extreme right to which I earlier referred. He would not be an attractive choice for that large center which I also mentioned. With our paper ballots in hand, little did we know…

Shift your focus, if you will, to the city of New Orleans. Several months before the Houston convention, two other right-wing extremists, Paige Patterson, once pastor of First Baptist in Fayetteville, and Paul Pressler, a judge in Houston, met at the Café Dumond in NOLA to plot their political takeover of the SBC. How best to move this huge denomination to the right where they could control her destiny? It could only be accomplished through electing their man—and obviously, it would be a man—to the presidency. The president of the convention had the power to determine who would serve on the various committees, commissions, and agencies that made policy for the SBC. Not only was there power to be grasped, but millions of dollars and properties as well, including two large encampments and six theological seminaries. The Sunday School Board alone had its very own zip code in Nashville. There was a lot at stake. It would take time to accomplish their purposes, Patterson and Pressler agreed, but it was worth it for the sake of what they felt was the spiritual goal of “saving” the convention from liberal destruction.

We were a people without a denominational home.

The leaders of the right-wing takeover movement felt the denomination should reflect their views, not that of those who were in the center or the left. And so, for the very first time in the history of the convention (at least for the very first known time), raw politics was used to get their way.

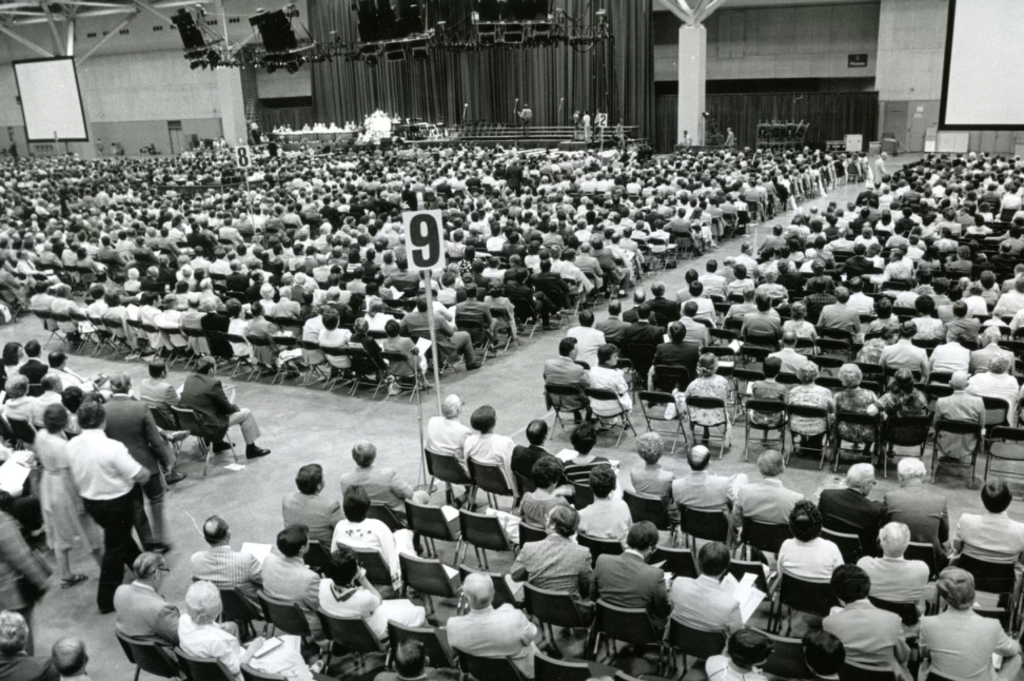

Based on the size of a church’s membership and gifts to the Cooperative Program, each congregation was allowed to send a certain number of delegates (called “messengers”) to the convention meeting. Except for very small congregations, many if not most churches were allowed the maximum of ten messengers. Annual convention meetings, especially when a presidential election took place, would see thousands of Southern Baptists assembled in one place. This gave rise to the saying that when they were in town there were two things Southern Baptists would not break: the Ten Commandments and a ten-dollar bill.

Patterson and Pressler arranged for like-minded churches to send their full equivalent of ten messengers, and they came literally by the busload. And they all voted in lock-step as they were instructed by zone captains dressed in navy blazers and red ties. Not only was Adrian Rogers elected, but on the first ballot, a rarity in SBC life. I turned to my friend Randel in utter disbelief, and he said to me, “Hyde, we’re in big trouble.” And then, those messengers who voted for Rogers were loaded back on their buses and sent home. They were not in Houston for the regular convention proceedings but for the purpose of voting for their man. As I said, it was a show of raw politics, never before seen in Southern Baptist life. Little did we know…

It took a decade, but it happened. Fundamentalism eventually became the capstone of the Southern Baptist Convention. Rogers was followed by a lineup of like-minded fundamentalists who kept the momentum going: Bailey Smith (an Arkansas native and fellow OBU alum), Jimmy Draper, Charles Stanley, Jerry Vines, and Morris Chapman, all pastors of large churches which, ironically, had a history of giving little or nothing to the Cooperative Program. During the decade of the 80’s, people like me worked to overcome the gradual takeover of our denomination, but by 1991 the battle was over and we acceded to our loss. We were a people without a denominational home, for the SBC no longer reflected our collective values.

What to do next? If you have stayed with me thus far in this narrative, perhaps you will be interested in my next piece that will tell you about the birth and life of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship.