Covid hit at a time when I was trying desperately to rebuild my relationship with my parents, particularly my mother. Almost three years later, all I can think about is how much I used to hate going home. I don’t hate going home anymore. In fact I long for it. But not as it is—as it was.

I dream of the days before my mom’s health completely deteriorated; before my grandmother’s partner of thirty-plus years lost her battle with lung cancer; before my beautiful grandmother herself passed away unexpectedly; before my papa withered after years of fighting cancer, too.

Before my parent’s house literally started falling apart at the seams.

With insulation exposed, drywall falling and floor sagging, the twenty-some-year-old trailer that we built our lives in is now decaying. And there’s nothing I can do to fix it. I used to think the trailer was a metaphor for my mom’s mental and physical state, as twisted as that seems. Lupus. Fibromyalgia. Depression. Anxiety. Agoraphobia for most of my teen life, rotting away in her room and relying on her child for any and all sustenance. In fact, most of my life my mom communicated via whistling for me, as if I were an animal she wanted to train. This was especially a point of contention with my father, although he never said anything to her directly. I guess it worked, because I knew exactly what to do when her shrill pitch made its way down the nicotine-stained walls and in through the crack of my bedroom door.

I think I hated my mom until Covid happened. And I know how that sounds, but I need to be one hundred percent honest with myself here. As a teenager I didn’t understand the complexities of the human mind, much less something as damaging as Agoraphobia. To be fair, neither did my mom. In her mind she was okay, and our lives were “normal,” but the few friends I trusted enough to come over would tell me that her behavior was anything but. So I was forced to take on the role of my mother’s caretaker—long before she was wheelchair bound and on oxygen.

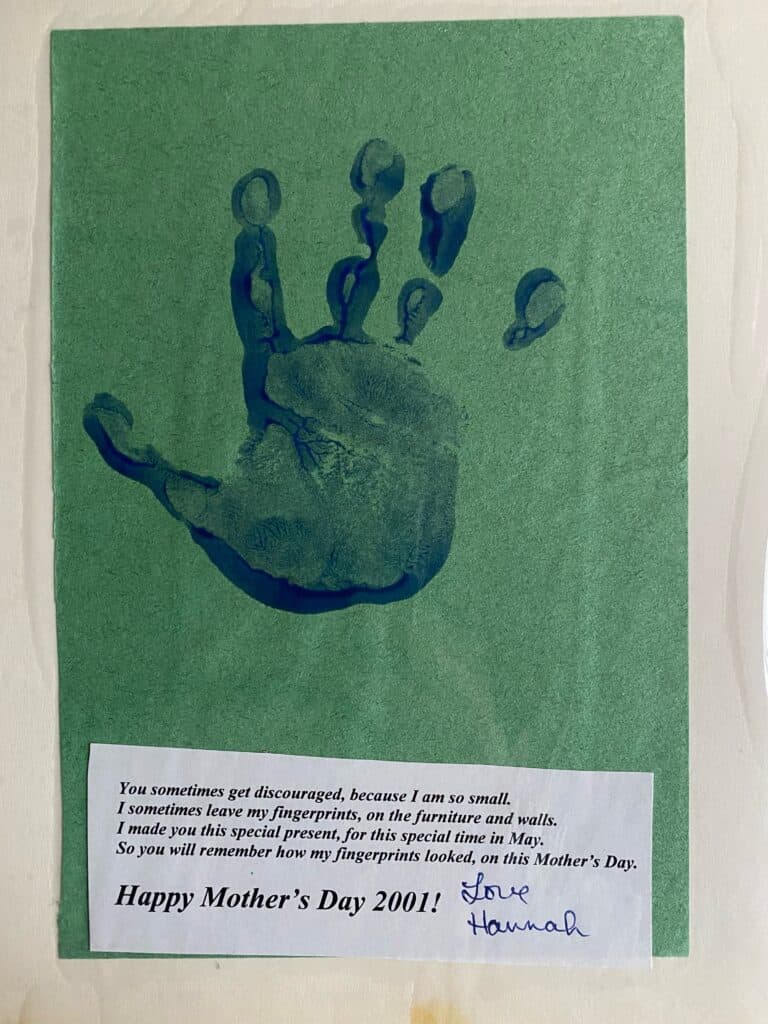

Now that I’m older I understand that she was afraid. In high school I often wondered what happened. She wasn’t always like this. We weren’t always like this.

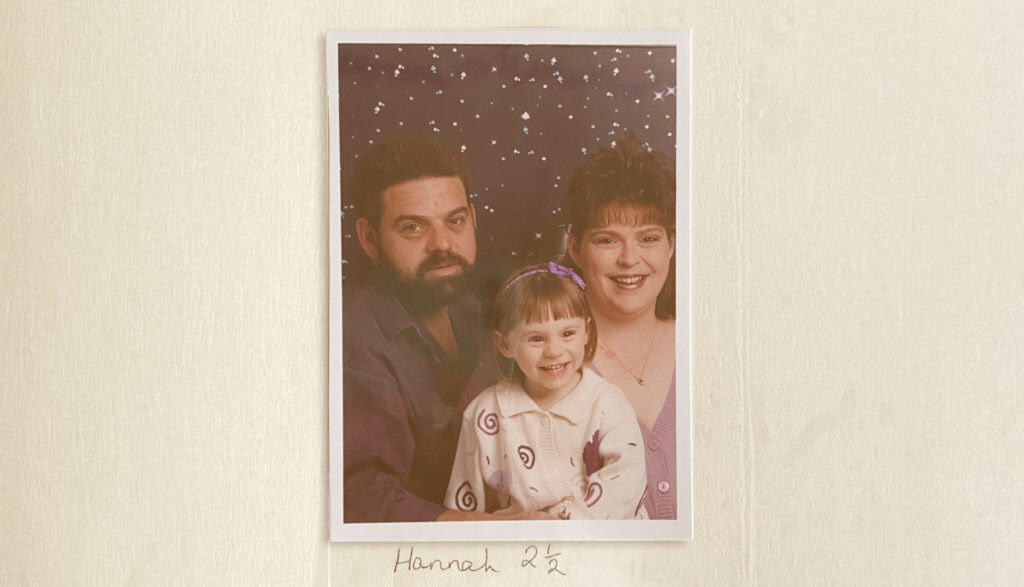

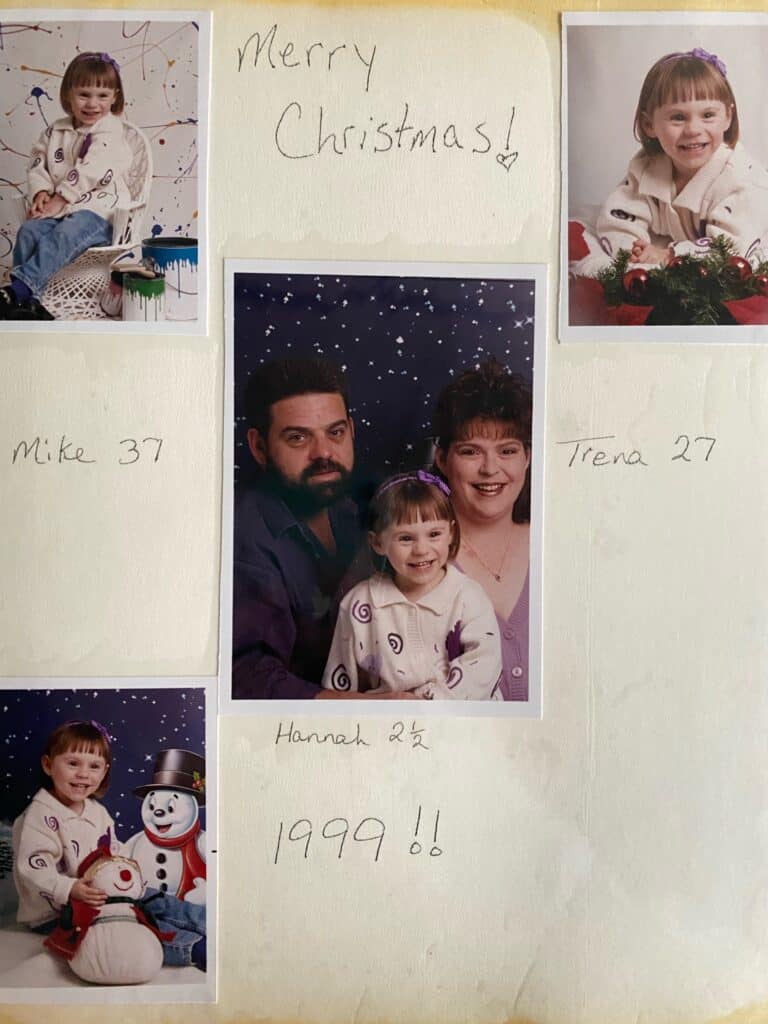

I grew up in Greenwood, in the same decaying trailer that now rests in Sheridan. My parents both worked in Fort Smith, and despite our financial troubles and Southern Baptist ties, they decided to send me to a small private school called First Lutheran. My mom told me she was bullied, and she blamed it on the “ungodliness” of public schools.

I felt the heat of hatred bubble up inside me. Guilt quickly turned to rage, and my mother would usually bear the brunt of it. Looking back, this is my biggest regret: directing all of my anger and frustration towards her, a woman who had already felt the blow of loved ones doubting her.

One of my earliest memories is my mom crying on my dad’s shoulder in a lawyer’s office while filing for bankruptcy. That’s the first time I felt this overwhelming feeling of grief just for being born. I didn’t know what was happening, but I knew I was somewhat responsible. Those feelings of guilt grew with every screaming match and fist-sized hole in the wall. I used to pray every night for my parent’s divorce. I thought they would be happier. I would often catch myself fantasizing about their lives without me. Would my dad be less angry? Would my mom feel heard? I didn’t think it could get worse, but it did, and it continued to spiral downward, where I’ve been until present day.

Mom put herself on the back burner for many years because I was born with Cerebral Palsy, a fact I would be oblivious to for years. Physical therapy, muscle relaxers, leg braces, and botox injections all ate away at most of our funds, not to mention that expensive private school tuition my mom insisted on paying. This left her to suffer with undiagnosed Lupus for more than five years. I watched as my family accused my mom of being lazy, of lying. I think this is what led to her negligence of her mental health, and to mine.

Following her diagnosis, things were better. I was happy to see my family smiling, but it didn’t last. Pretty soon after her diagnosis, we found out that my dad’s company was shutting down. They had already started laying people off. It was like a switch flipped, and we were back to where we started, except this time we were losing our main source of income as well as health benefits. Perhaps the worst part, at least to my mother, was the reality that she would be returning to a town she hated. The town of Sheridan had never accepted her, and now she was being forced to move back.

My dad and I weren’t happy about the move, either. We were a family of introverts, and we had built new friendships that none of us wanted to leave. I felt especially devastated knowing I’d be leaving my best friend Maddie. But there was no other option for my family.

I thought they would be happier. I would often catch myself fantasizing about their lives without me. Would my dad be less angry? Would my mom feel heard?

When we settled in Sheridan, a tidal wave of depression and anger tore through our aging trailer. I was sad all the time. I was mad. I felt the heat of hatred bubble up inside me. Guilt quickly turned to rage, and my mother would usually bear the brunt of it. Looking back, this is my biggest regret: directing all of my anger and frustration towards her, a woman who had already felt the blow of loved ones doubting her. And now, her only child had joined the bandwagon.

I know she would tell me none of this was my fault, but I can’t help but feel responsible for her falling into herself the way she did. It started slowly: not going to ball games, getting visibly angry when asked to leave the house, etc. When I got my driver’s permit, she would sit in the safety of her tinted windows while I bought groceries for the family. This was my least favorite errand of all, due to the number of times I had to leave a cart full of food at the checkout line because our bank card was declined. By the time I had my full license, she stopped leaving her room altogether. I can’t explain how this made me feel. Somedays the guilt would come back, and I was left in my room to ponder all the reasons my mom could have for hating me. And she was asking herself the same questions about me.

Fast forward to 2019: I’ve been on my own for five years, and my mom and I are finally able to have a conversation that lasts longer than two minutes. A miracle. She had started taking antidepressants, and for the first time in my life, I was able to see past the walls and into her true self. But her years of being docile were unkind. We took a trip to see my Oma’s grave in Texas, but my mom couldn’t walk longer than a minute at a time. The most heartbroken I’ve ever felt was seeing her cry as I proudly pushed her around Texas. She called herself a burden, and in that moment, everything clicked. My mom had spent all of her adult life feeling like she didn’t deserve anything. Love, compassion, trust…just like me.

When I got home from the trip, I spent a week in my room sobbing over the revelation. Who was I to have been so quick to judge? After all, in the five years I spent away from home, I’m pretty sure I spent a quarter or more of that time cooped up in my room surrounded by half-empty soda cans, chip bags and dirty dishes—a scene I grew accustomed to when taking care of my agoraphobic mom.

Shortly after the trip, the world was brought to its knees by a deadly pandemic. The day the first case was reported in Arkansas, I called my mom. My heart dropped. She had been in the hospital with pneumonia. She said she didn’t want to worry me, but in that moment I felt the weight of my culpability. I could hear the absolute pain in her voice and the soft hum of the oxygen machine keeping her alive in the background. I made it my personal mission to ensure her safety.

At that moment I wanted nothing more than to be in that broken home, taking care of my mom like I’ve done my whole life.