Editor’s Note: This story is the first of two reflections from Carmie Henry on Johnny Cash’s enduring Arkansas legacy. To honor Johnny Cash Day on February 26, we’ll continue Carmie’s story, sharing his behind-the-scenes take on the preservation of Cash’s boyhood home in Dyess. Featured image courtesy of the Architect of the Capitol.

A lifelong fan who helped preserve the Cash legacy reflects on the honor of witnessing the historic Capitol statue unveiling.

Written by Carmie Henry

Sitting among the 700 people in attendance last September in Emancipation Hall at the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center, I felt awestruck. I absorbed the solemnity of the ceremonial unveiling of the statue of Johnny Cash that represents the state of Arkansas in our nation’s capitol building. It was different from the awesome feeling the first time I saw him perform live in the fall of 1965 at a tiny high school basketball gymnasium in Bryan, Texas. But awestruck it was, both times.

The man had presence.

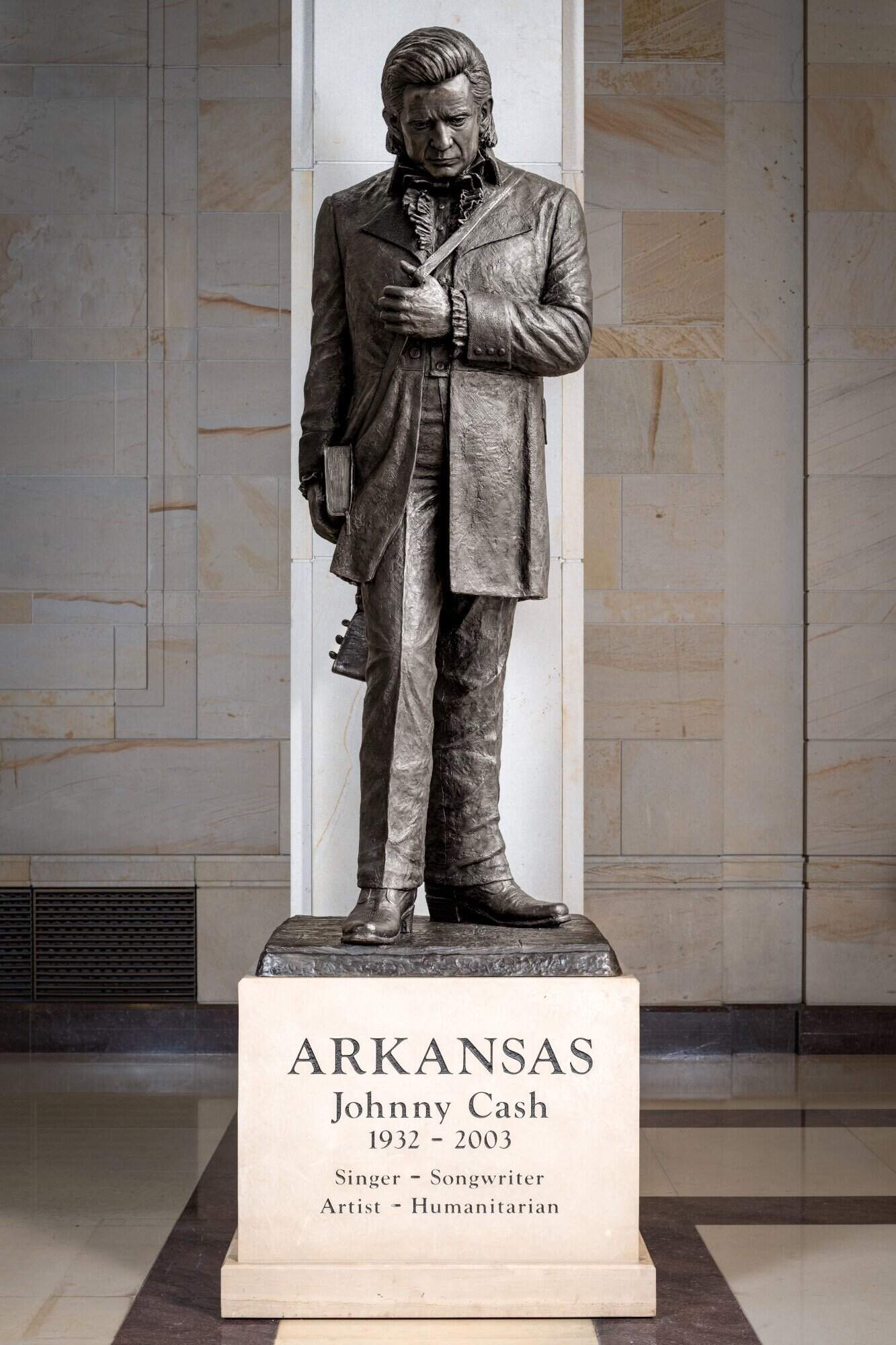

The statue was cast at The Crucible in Oklahoma and stands on a pedestal clad with tan limestone from Eureka Springs, Arkansas, with a total height of nearly 11 feet. Photograph courtesy of the Architect of the Capitol; September 24, 2024.

The inscription on the front of the pedestal provides an overview of Cash’s life:

ARKANSAS

Johnny Cash

1932–2003

Singer – Songwriter

Artist – Humanitarian

The proper right side of the pedestal is inscribed with lyrics from Cash’s song “The Man in Black,” often cited as a prime example of his solidarity for a wide range of marginalized people:

“I wear the black for the poor and

the beaten down

livin’ in the hopeless, hungry

side of town

I wear it for the prisoner who has

long paid for his crime,

but is there because he’s a victim

of the times”

On the proper left side, the inscription is something Cash used to say to his children:

“All your life you will be faced

with a choice. You can choose

love or hate.

I choose love.”

Johnny Cash has been a presence in my life almost from the beginning. I heard his early songs, recorded at Sun Records in Memphis, on the radio as a young boy in the 1950s. Back then I didn’t know what he looked like, but I could recognize that voice locked in a dark closet. I recognized that boom chicka boom guitar sound, too.

There was just no one else who sounded like that.

The ceremony in the Capitol Visitors Center felt like the right conclusion to the life and legacy of this man from Arkansas. More than 100 Cash family members were in attendance for the packed ceremony. The words of the Speaker of the House of Representatives Mike Johnson felt right, too.

Today we have the pleasure of recognizing—get this—the first musician to ever be honored with a statue here at the Capitol. Johnny Cash is the perfect person to be honored in that way. He was a man who embodied the American spirit in a way that few could. He was an everyday man. He loved to fish and he suffered the pain of loss. He was the son of Southern farmers and of the Great Depression. Americans related to Johnny Cash, so families across the country invited him into their homes through their radios and their record players. Because the ‘man in black’ sung of tragedies of life and the difficulties that Americans faced, he provided Americans hope.

Johnny Cash met six sitting U.S. Presidents during his long career. He performed for President Richard Nixon at the White House in April 1970 and later met again in July 1972 to discuss prison reform. President Gerald Ford met with him in November 1975 after Johnny sent a letter supporting Ford’s pardons. In June 1977, Johnny and June visited President Carter, a distant cousin of June and a friend of Johnny. President Ronald Reagan met with them in the White House in 1988. President Bill Clinton hosted him during Kennedy Center Honors in 1996 with a reception in the East Room. Johnny received the National Medal of Arts from President George W. Bush in 2002.

Every state gets two statues to honor citizens, and many of the statues one sees when touring the capitol are of senators and congressmen, governors and the occasional president. Speaker Johnson said it was appropriate that ordinary citizens who contribute to the public life and culture of our nation should be recognized.

Johnny Cash was no ordinary man.

Johnny’s Grammy-winning daughter, Rosanne, said it best in her speech at the ceremony. “He was a flawed but profoundly humble, kind and compassionate man with a magnificent generosity of spirit, who loved those who suffered because he knew great suffering and loss,” she said. “He was passionate in his work for the rights of prisoners, the rights of Native Americans, for impoverished children and for all those who struggled and whose prospects were dim.”

Left to right: Jerry Smith, sculptor Kevin Kresse, and Carmie Henry.

We unveiled two new statues in the capitol last year. Johnny Cash and Daisy Bates. One man, one woman. One white, one Black. Both raised in the poverty of rural Arkansas. Both famous fighters in their own ways for the downtrodden in our society. Neither ever elected to public office. Both deserve respect regardless of any personal human flaws they may have had.

As I sat in the audience that day I thought of Bill Clinton. It could have been his statue we were unveiling that day. He’s a famous Arkansan who rose to the greatest heights—but I think Arkansas has gotten it right.

How many times have I driven in my car across the country listening to Johnny? I even listened when I was on a Navy ship in the Gulf of Tonkin after a day of flying combat missions.

I knew Johnny Cash was going to be successful. I just didn’t know how long it would last or how hard that road would be. Johnny Cash was all over America singing his way into our hearts on radio and television, in huge stadiums, at Billy Graham’s crusades.

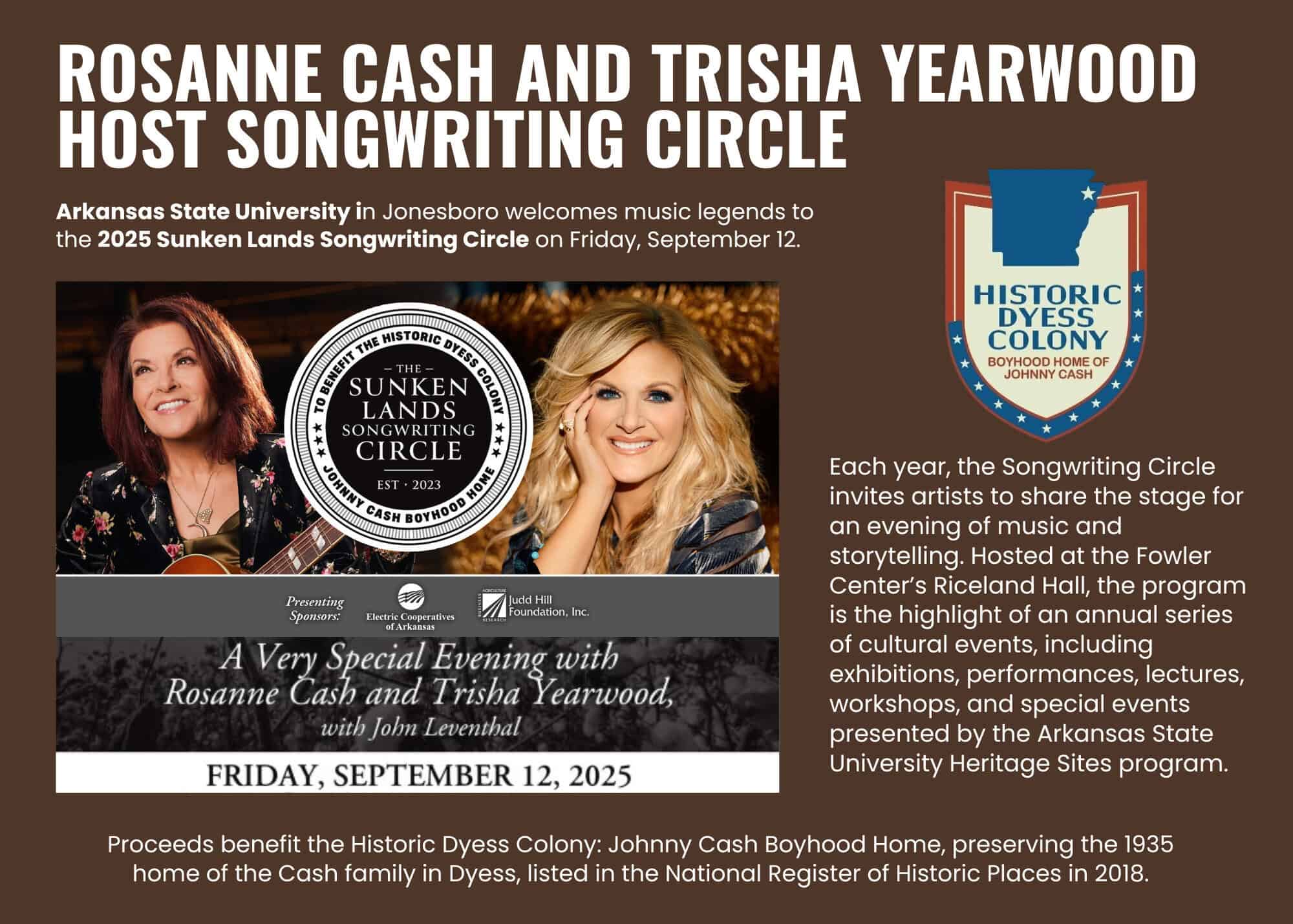

At that unveiling ceremony in the nation’s capitol I ran across a woman I adore, Dr. Ruth Hawkins, recently retired from the faculty at Arkansas State University in Jonesboro. I told Ruth we would not be there if not for her. She repaid my compliment, saying I caused us to be there. It’s true: my colleague Kirkley Thomas and I were the ones that brought the Johnny Cash boyhood home project to her attention. That is a story all its own and certainly one worth sharing.

Lifelong Arkansan Carmie Henry has more than 22 years of experience on the staffs of three United States senators and an Arkansas Secretary of State. He received a bachelor’s degree in accounting from the University of Central Arkansas, and is a retired Naval flight officer with the rank of captain. He is pictured inside the childhood home of Johnny Cash in Dyess, Arkansas, he helped preserve.