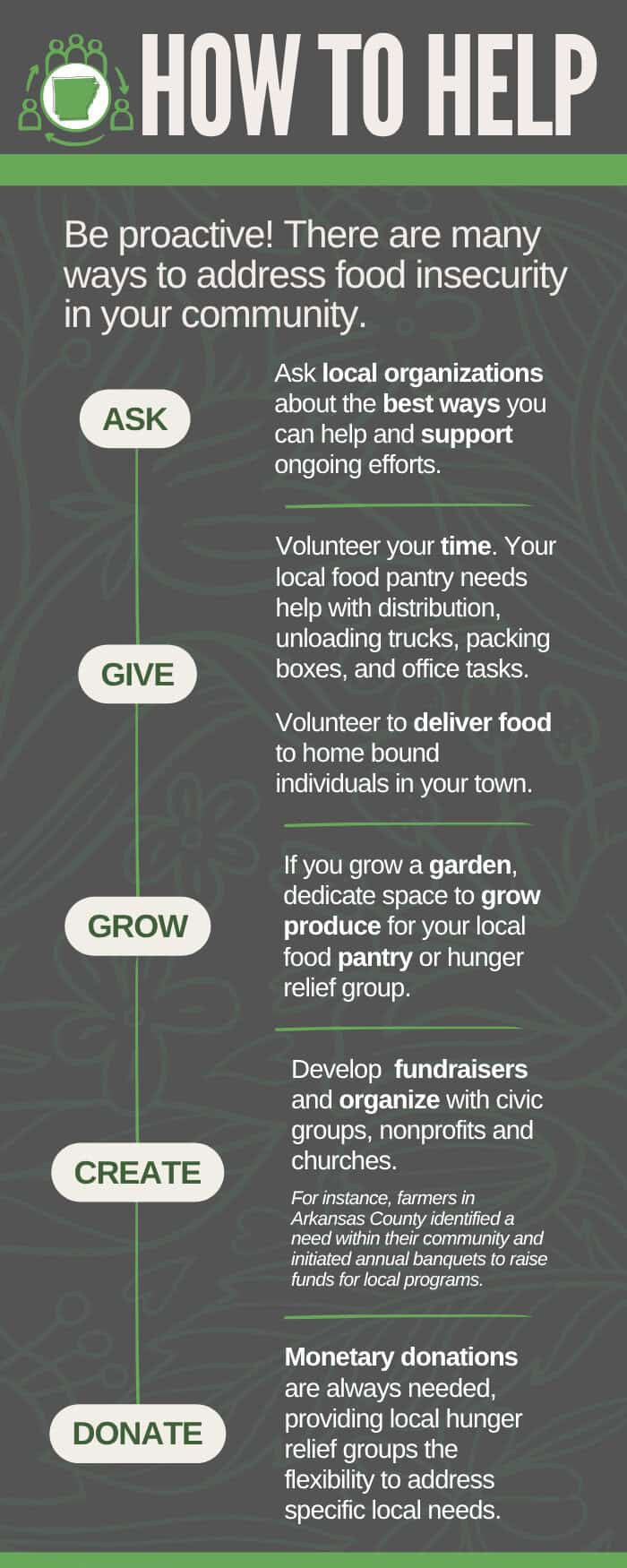

Once-reliable government safety nets are shrinking, and local efforts are straining under the pressure. The systems that once buffered communities from hunger are fading—just as the need for them grows.

The Paradox of Plenty in a Hungry State

Arkansas is primarily a rural agricultural state. Grain elevators often overflow with rice, soybeans and wheat. Despite this abundance, nearby neighborhoods often face some of the highest rates of food insecurity in the state. Although food production is a major industry, Arkansas paradoxically remains one of the hungriest states in the nation, and trends suggest this hunger will continue.

With a food insecurity rate of 19%, Arkansas’s food security rates are the worst in the nation, ranked 50th out of 50 states (Rabbitt et al., 2024). Food security is described as everyone in a household having constant access to enough food to live an active, healthy life (United States Department of Agriculture [USDA, 2021]). Unfortunately, many people in Arkansas also struggle to meet other basic needs, increasing their food security risk (Borger et al., 2014). Among households with incomes below 185% of the poverty line, 26.5% are food insecure (USDA, 2021).

The Struggle to Meet Demand

Local organizations, both secular and faith based, work to address food insecurity by making more food available. Some of these strategies include enrollment in government programs, food banks and pantries, home and community gardens, farmers’ markets, and food kitchens. However, current efforts are being overwhelmed. Government no longer provides some of the same safety nets once seen as the critical link to assistance. Currently, the options we have had in the past are being challenged.

One leader stated, “I am overwhelmed and tired.” Another echoed the same sentiments, noting, “everyone seems so tired.”

The Arkansas Advocate reported that USDA cut over $1 billion from food bank and school meal programs, including $660 million previously allocated for schoolchildren. The Local Food Purchase Assistance and Local Food for Schools programs connected schools and food pantries with local farms, benefiting small farmers and providing quality nutrition to children. United States Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins called the programs “nonessential.”

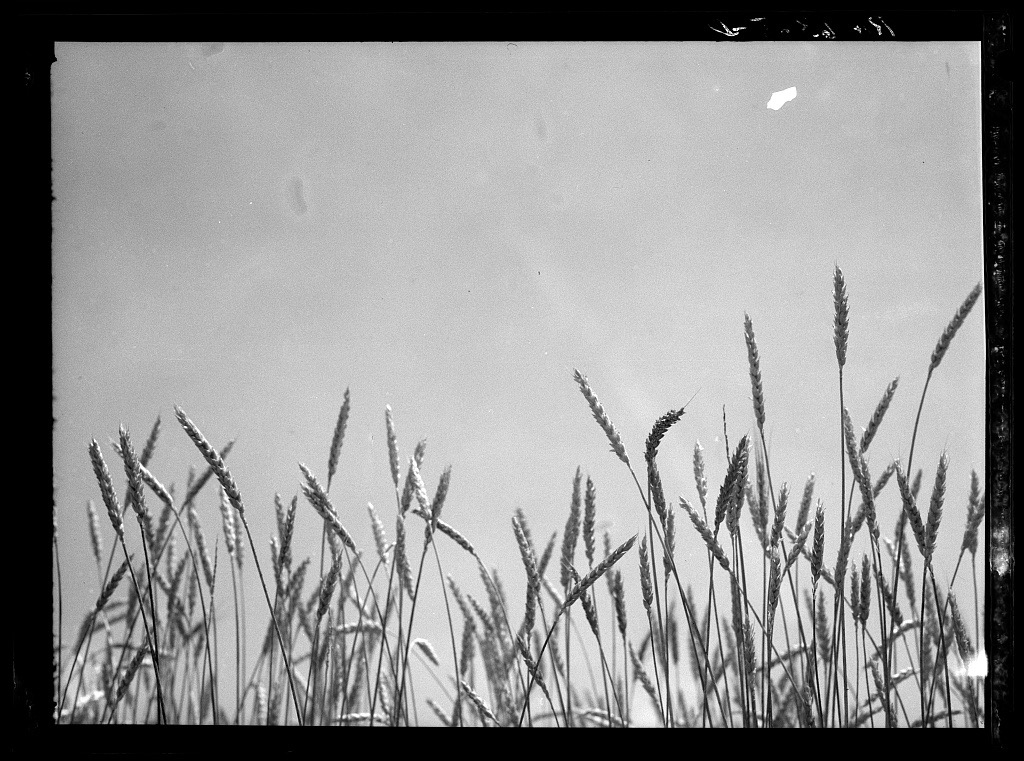

These photographs, courtesy of the Library of Congress, taken in June of 1936 by Farm Security Administration photographer Carl Mydans near Batesville, Arkansas, show early federal efforts to address rural hunger. Left to right: Batesville, Arkansas. Wheat Tops; Rehabilitation client and food canned at the suggestion of Resettlement Administration rehabilitation supervisor. Near Batesville, Arkansas; Resettlement Administration rehabilitation loan supervisor talking with client on potato raising problems. Near Batesville, Arkansas.

Community Response to Hunger

Recently, I conducted a research study examining the attitudes and management strategies of rural community leaders concerning food insecurity at the local level. Local leaders throughout Arkansas were interviewed and their responses analyzed for concurrent themes (Boles, 2023). In these discussions, local leaders described food insecurity not as a single issue but as the result of a variety of issues, with poverty being the common factor. In Arkansas, it can be the size of the county and the distance to a grocery store. It can be the cost of gasoline. It can be the poor conditions of dirt roads and geographic isolation. Many in both rural and urban environments may not have transportation or are in too poor health to make the trip to the grocery store. The clustered disadvantage of poverty, not food availability alone, was seen as the source of food insecurity.

Several themes were expressed by the participants in the research study.

COMPASSION

Local leaders cared about their community and wanted to help. One leader noted, “There is much compassion within the community. Local leaders have compassion and awareness of what is happening in this community. They care for the people.” Another stated “We are always trying to think of things to improve our community,” and added, “Leaders believe they are supposed to help their neighbors and love them as you love yourself” (Boles, 2023).

AWARENESS

To lead effectively, local leaders must be a part of the community they serve. Leaders must be actively involved, participate in, and understand their community; know the parents, grandparents and the children; know if portions of the people are food insecure. In Arkansas, efficient food systems only result from understanding the culture (Alexander, 2016). When awareness is combined with caring, it motivates action resulting in assistance. Community leaders emphasize determination and resilience: “Make up your mind that this is what you want and set your goals and then do not let anybody change your mind about it. Keep after it.” (Boles, 2023).

INCLUSIVE COLLABORATION

To address the scale and nuances of food insecurity local leaders must engage with diverse populations, leveraging others’ expertise and resources. “It is not something made by leadership and assigned to an individual. It is more organic, more just from the ground up. It is just talking and networking with others and getting ideas from other communities”. (Boles, 2023). In many cases, collaborations are with individuals and groups different than us. The need for an open mind to engage with individuals and groups providing diverse expertise and resources is an attribute of leadership. Leaders need to be “open-minded” and “willing to do something” because community leaders know that “things needed to happen and quickly” in such “dire situations.” (Boles 2023). Additionally, being open and flexible may mean going beyond grant-funded activities.

The Tontitown Grape Festival’s spaghetti supper is a long-standing example of grassroots fundraising and neighborly support. This year’s festival, scheduled for August 5-9, is believed to be the longest-running annual community celebration in Arkansas. Images courtesy of the Library of Congress, 1941, America Eats, Federal Writers Project.

The Overwhelming Nature of the Issue

Local community efforts are accompanied by feelings of being swamped by the complexity of food insecurity. Although local leaders are aware of and assist those facing food insecurity, the issue is far from resolved. Their efforts seem futile. As a result, they reported becoming befuddled and overwhelmed. Several local leaders spoke of wanting to serve their community but feeling exhausted by the scale of the work and the nuances of the challenge. One leader stated, “I am overwhelmed and tired.”, Another echoed the same sentiments, noting, “everyone seems so tired.” (Boles, 2023)

Hungry Arkansans don’t just need our thoughts and prayers; they need our help.

Arkansas’s food security rates are the worst in the nation. Arkansans are hungry because they can’t afford or easily access food. Poverty is ultimately the cause of food insecurity, and to affect food insecurity long-term, we must address poverty. However, people are hungry now. People need assistance at the local level at present. Government programs, food banks and pantries, community gardens, farmers’ markets, and food kitchens help ensure people are fed. Local leaders may be compassionate, aware of the issues within communities, and work inclusively with a diverse number of organizations, but the work can be exhausting. Local communities need help in the form of leadership, labor, supplies, and food donations. Your local community needs you.

Faith based organizations operate 77% of the food pantries in Arkansas.

JAMES 2:15-16: “If a brother or sister be naked, and destitute of daily food, and one of you say unto them, depart in peace, be ye warmed and filled; not withstanding ye give them not those things which are needful to the body; what doth it profit?”

Hungry Arkansans don’t just need our thoughts and prayers; they need our help. This is a call to action for us all to acknowledge and commit to our moral and civic responsibility of serving our neighbor and our community.

Do not give up that good fight. You are probably not going to see the results. You will not get those magical moments until you put the work in, but slowly and surely, you can make a difference. However, it may be one individual at a time instead of one county at a time (Boles, 2023).

We can make a difference, one hungry person at a time.

If you or someone you know needs food assistance in Arkansas, contact one of the state’s six regional food banks below for help locating local pantries and food distribution sites.

| Arkansas Foodbank Central Arkansas | arkansasfoodbank.org | 501-565-8121 |

| Northwest Arkansas Food Bank Springdale | nwafoodbank.org | 479-872-8774 |

| Food Bank of Northeast Arkansas Jonesboro | foodbankofnea.org | 870-932-3663 |

| Food Bank of North Central Arkansas Mountain Home | foodbanknca.org | 870-499-7565 |

| River Valley Regional Food Bank Fort Smith | rvrfoodbank.org | 479-785-0582 |

| Harvest Regional Food Bank Texarkana | harvestregionalfoodbank.org | 870-774-1398 |

Sources

- Alexander, S. (2016). Hope in the Hills: How communities can feed hungry children in the rural Ozarks of Arkansas. Hendrix College.

- Hennigan, M. (2024) Food insecurity in Arkansas worsens, rate ranks second highest nationwide: Issue transcends rural and urban areas, people living in poverty and the ALICE population. Arkansas Advocate.

- Boles, J. (2023). Community Leadership, Food Security, and Capability in Arkansas. University of Central Arkansas.

- Borger, C., Kinne, A., O’Leary, M., Zedlewski, S., DelVecchio Dys, T., Mills, G., Watsula, D., Engelhard, E., Montaquila, J., Waxman, E., Hake, M., Morgan, B., & Weinfield, N. (2014). Feeding America Hunger in America 2014 National Report. Feeding America.

- Rabbitt, M. P., Reed-Jones, M., Hales, L. J., & Burke, M. P. (2024). Household food security in the United States in 2023 (Report No. ERR-337). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- United States Department of Agriculture. (2021). ERS key statistics and graphics.

FEATURED IMAGE: Delta plantation landscape south of Wilson, Arkansas, by Farm Security Administration photographer Dorothea Lange, August 1938; Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Dr. Jack Boles began his career with the UA Cooperative Extension Service in 1987 where he served in a variety of positions, from County Extension Agent in Independence, Arkansas and Newton counties to serving as the Environmental Management Specialist for agricultural issues. He retired with Emeritus status from Extension in 2013 and served as Executive Director for the State 4-H Foundation. After retirement, Jack went back to school and received his doctorate in Interdisciplinary Leadership from the University of Central Arkansas. His research interest in leadership and food security is based on his experiences as a county agent in Arkansas and as a volunteer livestock specialist in Bangladesh, Cambodia and Indonesia. Jack is an advocate for food security, small farms and local farmers; and along with his wife Lisa, works to promote peaceful communities through their organization The Dove’s Nest Project.